Urban heat islands, cool roofing, and the impact on people

Coil coating producers in the U.S. have been supplying “cool roof” coatings for over two decades. These coatings are specifically designed to reflect the sun’s rays back into the atmosphere rather than absorbing them like many typical roofing materials. The theory goes that, by doing this, cool roofs help keep buildings cooler, lessen the reliance on air conditioning, and improve energy efficiency and overall quality of life for building inhabitants. Research backs up these claims.

There is even evidence that cool roofs can improve quality of life for a city’s entire population. The urban heat island effect is named for the higher temperatures experienced in cities due to their concentrations of man-made surfaces such as buildings, sidewalks, and streets. It is especially vexing during the summer, and economically disadvantaged communities often bear the brunt.

Many of us retreat inside our nice, cool homes during a brutal heat spell, but many others have no means to do so. You might think the urban heat islands are found exclusively in southern cities of the U.S., but any metropolis where buildings, parking lots, and streets have replaced grass and trees experiences this heating effect.

Because cool roofs redirect the heat from the sun away from buildings and back into the atmosphere, they help to mitigate the heat island effect.

They can even act a literal lifesaver.

The Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center has conducted research on how cool roof technologies benefit the lives of people living in metropolitan areas, and how lives are saved in the process. The research conducted by a collaboration of institutions offers convincing data to back up this statement.

These are the primary conclusions from the research:

- Heat is the leading weather-related cause of death, greater than hurricanes, tornados, and forest fires … combined!

- Summer climate variability is more important than the actual temperature. Chicago experienced its worst heat-related deaths in 1995 (July 12-15) due to a sudden heat wave, coupled with high humidity. In contrast, Phoenix, as an example, is always hot (and dry, of course), and people living there are prepared to handle the heat since it is an everyday issue. Chicagoans, on the other hand, were unprepared.

- It’s not just hot daytime hours that are a problem. So are excessive nighttime temperatures.

- Weather conditions, rather than simply the temperature, provide a more appropriate perspective, as well as an early warning system to help people prepare. Two oppressive conditions were identified:

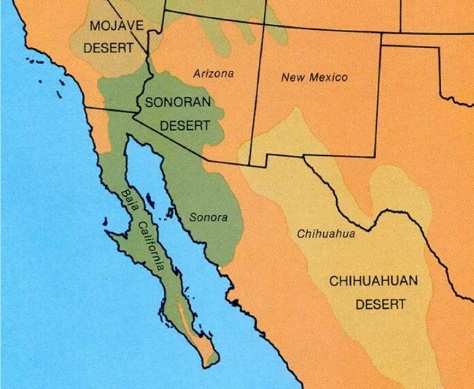

- Dry tropical conditions, usually associated with an air mass being transported from a desert region, such as the Sonoran Desert.

Source: U.S. National Park Service

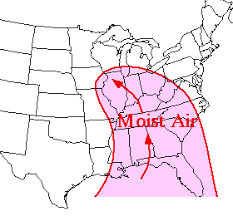

- Moist tropical conditions, with air masses bringing tropical air from the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Seas. This condition produces a high “heat index.”

Source: University of Illinois, Department of Atmospheric Sciences

- Mean mortality was modeled using historical climate data for many cities. The model is now used by several cities to predict, based on weather forecasts, the severity of a heat wave, and which appropriate actions may be taken to protect the public.

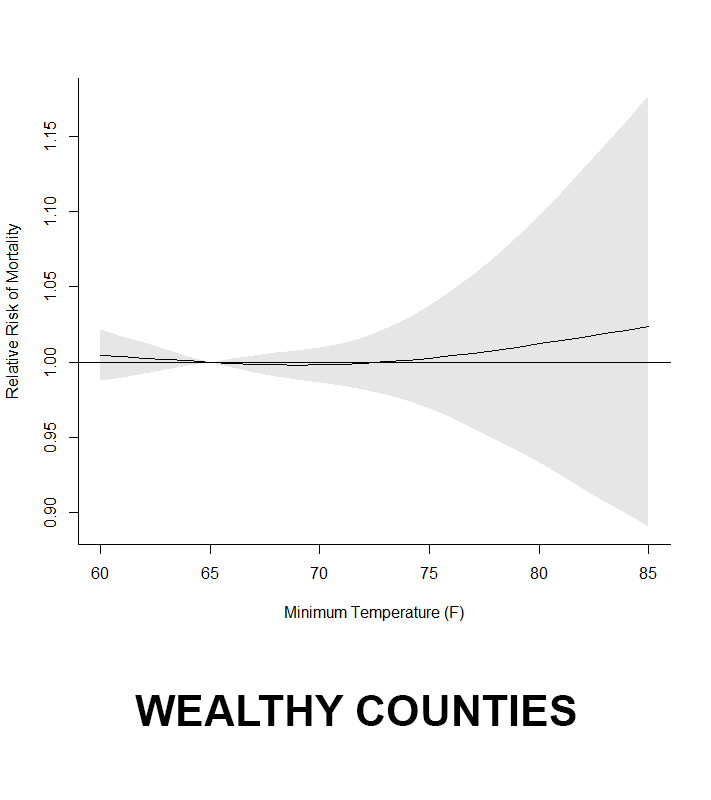

The foundation worked with 3M (a manufacturer of roofing granules used in the production of shingles), UCLA, Arizona State University, and the Cool Roof Rating Council (CRRC) to develop data for the aforementioned model. In addition to serving as an early warning system, the same data was used to evaluate a few neighborhoods in Chicago, comparing wealthy counties to two other much poorer counties, Cook County, Ill., and Lake County, Ind.

Since the X-axes are the same scale (minimum temperature in degrees Fahrenheit), a simple visual observation of the above graphs shows that, as the temperature rises in wealthy counties, the increased risk of mortality is minimal. In the two other counties studied, the relative risk increases sharply as the temperature increases. A portion of this is related to the increased temperature in these two counties due to the Urban Heat Island Effect being greater than in the wealthy counties. It also demonstrates that those living in disadvantaged communities have fewer options to escape the heat.

The work with 3M, et al., further concludes that “cool shingles,” using 3M’s IR-reflecting granules, reduce heat transfer into a building and lower the temperature of the heat island. Although this work studied steep-slope roofing with shingles, the same can be said about steep-slope metal roofing, since both cool shingles and cool roofs use similar technology to reflect heat from the sun back into the atmosphere.

“Cool” roofs and walls provide immediate heat relief, improve health outcomes, reduce air-conditioning use, and lower energy bills. To learn more about cool roofs and walls, access NCCA’s Tool Kit #38 or visit the CRRC’s website.

The information in this blog is attributed to Dr. Laurence Kalkstein, Chief Heat Science Advisory for the Arsht Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center as part of the newly formed Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance (EHRA). Dr. Kalkstein works with several organizations and is a strong advocate to increase heat resilience in urban areas, focusing on vulnerable populations.